Monday, September 12, 2005

20 Things They Don't Want You to Know

Posted Thursday, August 25, 2005

Psssst! Wanna know a secret? How about a whole bunch of them? Sadly, the Colonel's Secret Recipe and Dick Cheney's Secure Undisclosed Location remain shrouded in mystery, but I'm going to spill the beans about a bunch of things that technology companies would rather you didn't know. These insider tips will help you cut through hype when you shop, save money when you buy, and get the most out of products you already own.

Here's a CPU manufacturing secret: Most CPUs can be overclocked to run at least a bit faster than usual, giving your PC a free speed boost. And on some rare occasions, low-end chips are capable of running just as fast as much more highly priced CPUs. But while overclocking can speed up your system, note that you must take care to properly cool your PC, or you might damage the CPU--and most system warranties won't cover that damage.

The big speed jumps usually come along when Intel or AMD has transitioned to a new manufacturing process and is getting great yields on even its high-end chips. When that happens, slower CPUs that use the same technology are ripe for overclocking. The classic example: Intel's Celeron 300A chip, a 300-MHz CPU that overclockers routinely ran at 450 MHz. Check in periodically with enthusiast sites like Anandtech (and HardOCP--they go wild when those situations arise.

To overclock most of today's CPUs, you bump up your computer's bus speed, either through the system's PC Setup (or BIOS) program or via a Windows-based utility such as NVidia's NTune. (See "Secret Tweaks" in our March 2005 issue.) Each time you increase the speed, you should use a utility like Motherboard Monitor to check the CPU's temperature while you stress the system by encoding video or playing a 3D game. If the core temperature rises above 60 degrees centigrade, or if you experience any system instability (crashes, corrupt graphics, etc.), roll back to the next-lowest setting and stay there.

Read more:

- You Never Have to Pay Full Price

- Faster Shipping Isn't Always Faster

- You Can Kill the Messenger

- Extended Warranties Aren't Worth It

- You Too Can Exploit Windows' Bad Security

- You Can Save Big Money on Big-Name Software Packages

- That Dead Pixel on Your LCD May Not Be Covered

- Your Cell Phone's Been Crippled

- High-End Manufacturers Don't Always Make Their Products

- You Can Call Amazon, EBay, and Other Web Businesses

- Security Center Can Be Muted

- Game Consoles Are Hackable

- You Can Use an IPod to Move Music

- You Can Get a Human on the Phone

- MP3 Players Run Down Too Fast

- Useless Specs

With so many ways to shop online, finding the best deal can be difficult--even at a major retailer such as Dell. The Bottom Line: If you're patient, or even just willing to look around, you should never have to pay full price for most tech products. Here are my favorite tips:

- When shopping at Dell, always check both the Home & Home Office and the Small Business sections. Prices for the same item often differ because independently operated business units manage these sections. Neither one consistently offers better deals, so when looking for specific items, check both areas periodically.

- If the product you're looking for isn't on sale, wait. Dell rotates promotional offers with blinding speed. Dell-branded products go on sale more often than items by other manufacturers do, but none of the products I tracked stayed at full price for longer than three weeks.

- The maximum discounts I've seen Dell offer--around 35 percent on its own items--are rare. But discounts of up to 20 percent on Dell-branded products and 10 percent on third-party items appear frequently.

- Deals on desktop and notebook PCs can be tough to evaluate, since Dell may also offer specials or free upgrades for included components (typically RAM, hard drives, and optical drives), making it difficult to calculate total savings on a system purchase. But sometimes you can find both discounts and free upgrades: In late July, for example, Dell offered a 34 percent discount on its XPS Gen 5 desktop, as well as a free upgrade from 512MB to 1GB of RAM.

- Check sites such as StealDeals.net and Techbargains.com (full disclosure: Techbargains powers PCWorld.com's Bargain Finder), which track day-to-day bargains on lots of shopping sites and which also list coupon codes that can augment the deals you find.

Not all deals are as good as they initially sound. Dell, for example, sometimes offers as much as $750 off notebooks that originally cost $1500 and up. But check the configuration and prices for notebook components carefully: Often the cost of adding RAM or a DVD burner will rise sharply during the deal period, cutting into your savings.

And before heading to a brick-and-mortar store, check the prices on its Web site at home, because local managers for chains such as Best Buy sometimes run in-store promotions that can produce prices different from those you'd see outside the store.

Everyone wants new books, CDs, and DVDs delivered yesterday. But for some folks, standard shipping may be just as fast as expensive two-day service. Try this experiment with a recent release you can stand to wait for. Use free or standard shipping, and check the package-tracking link to see what location handles the order (most of your orders probably ship from the same place). Most new releases I've ordered here in San Francisco ship from Reno or Fernley, Nevada--and they arrive in two days without expedited shipping.

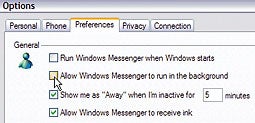

Know anyone who uses Windows Messenger as their instant messaging client? Me neither. Yet many of us have it sitting in our system tray anyway, because it often resurfaces even after you banish it using its own tools (select Tools, Options, click the Preferences tab, and uncheck 'Run Windows Messenger when Windows starts' and 'Allow Windows Messenger to run in the background'). You can, however, give Messenger the boot permanently; Click here for detailed instructions.

You know the drill: You're ready to pay for a new PC, HDTV, or peripheral, and take it home. But first you must suffer through your intrepid salesperson's 20-minute rap on why you'd be a fool to leave without buying an extended warranty. These plans are rarely a good deal.

Retailers push extended warranties hard because they're almost pure profit. By buying one, you're betting that your product will break, that the extended warranty will cover the damage, and that repairing the product would cost more than you paid for the extended warranty--an unlikely scenario. Extended warranties typically cost between 10 and 30 percent of a product's purchase price, so if these criteria don't hold true for one in every three to ten tech products you buy, routinely purchasing extended warranties will be a losing proposition for you.

Financial planners recommend making your purchase using a credit card that extends the manufacturer's warranty, and then putting the cost of the extended warranty into a repair or replacement fund. Often, by the time you need that money, you'll probably have saved enough to replace the nonworking tech product.

If you still want the extended service plan, read the fine print carefully; don't rely on the salesperson's assurances. Recognize that you're paying more for peace of mind (being prepared for the off chance something does go wrong) than service. And look for service plans that really do help. For example, some plans for rear-projection HDTVs cover the cost of replacing the backlight bulb, which you'll eventually have to do anyway.

My PC's firewall, antivirus scanner, spyware remover, pop-up blocker, and spam filter all agree: Windows is sorely lacking in PC security. That situation may not change until Windows Vista (formerly Longhorn) comes out sometime next year. Meanwhile here are a few ways to turn Windows' poor security to your advantage.

If you ever have to reinstall Windows, you'll need the license key that came with your copy. But that string of 25 random letters and numbers isn't always handy. You'd think that in a world where you can't use Windows without activating it, the code required to do so would be a well-guarded secret, but thanks to lax Windows security, a 252KB download--Magical Jelly Bean Software's free Keyfinder 1.41--will recover your license key in a snap. Just download and run the app, and write down your key. Now if only Keyfinder could find my Windows CD....

While your license key might be written down somewhere, your Web site passwords probably aren't. I've set Windows to remember a bunch of mine so that I don't have to figure out the right log-in and password every time I go to, say, Amazon.com. Still, my only record of the password is asterisked out on Amazon's site. Because Windows doesn't do much to secure those stored passwords, you can get them back using another download. Revelation 2 from Snadboy Software will reveal any asterisk-hidden passwords. (It's free, although the site asks for a donation if you keep the software.) A $15 utility called Aqua Deskperience pairs a similar password-revealing ability with some useful features such as a convenient screen grabber and the ability to copy text from any application (including those where a copy command isn't available).

Finally, if the password you've forgotten is your Windows XP administrator password--required for operations such as booting into Safe Mode--Microsoft has a knowledge base entry that will help you reset the password.

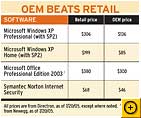

OEM: These three little letters, which stand for "original equipment manufacturer," can save you more than 50 percent on key software (see chart at left). Designed to accompany commercial systems, OEM editions have increasingly become available in stores such as Directron and Newegg. These stores are only supposed to sell OEM software with associated hardware--so for an operating system, you'd have to be buying parts for an entire PC. But most vendors let online stores sell OEM editions to anyone who buys a nonperipheral part--even a mouse, for example.

OEM software typically ships without a box, printed manuals, or the tech support you'd get with a retail version. But in return you save some serious coin.

Some monitor vendors are better than others when it comes to handling minor defects in their products. Any small anomaly in the manufacturing process can result in a dead or stuck pixel--a dot that stays bright or dark no matter what's being displayed. And since a typical 19-inch LCD has nearly 4 million tiny red, blue, and green subpixels, it's no surprise that some vendors balk at replacing a monitor if it has only a dead pixel or two.

But standards are improving. Philips's Perfect Panel guarantee and Asus's warranty for its V6V notebook display pledge replacements if even one pixel is dead.

Most vendors' LCD monitor warranties specify a minimum number of pixels that must be malfunctioning before they'll replace your display. Usually you can unearth a manufacturer's dead-pixel policy by searching its site for "dead pixels" or "pixel criteria." You might also find the policy in a PDF of the monitor's manual.

ViewSonic, for example, will replace a 14- to 15-inch monitor with more than four dead pixels; a 17- to 19-incher with seven dead pixels; and a 20-inch or greater monitor with more than ten stuck subpixels. Dell will replace monitors with six or more "fixed pixels"; NEC requires ten "missing dots." Most makers will also consider replacing a monitor that has a few dead pixels in a concentrated area.

To tether you to their service, carriers "lock" phones so you can't use them on a competitor's network. And sometimes carriers disable other features as well. But with a little time and effort (and spare change), you might be able to unlock your phone regardless of whether your carrier cooperates. Be aware, though, that doing so might invalidate your phone's warranty; read the fine print.

Why do carriers do this? Money. Service providers generally charge less for phones than third-party vendors do, and they need to recoup that money. So, for example, some carriers make it difficult for you to employ Bluetooth to let your phone act as a dial-up modem for a notebook or handheld (presumably to push you toward expensive over-the-air data services). Locked GSM phones also cost you money when traveling, as you can't swap out your SIM (Subscriber Identity Module, the tiny card that holds the phone number and other information specific to your handset) for one from a local carrier, which generally will charge less than most U.S. carriers do for overseas roaming.

The easiest and most common unlocking technique is to enter special numbers on the dial pad--typically an unlock code plus your handset's International Mobile Equipment Identifier (IMEI), Electronic Serial Number (ESN), or Master Subsidy Lock code (MSL). Some phones, including Samsung and Sony Ericsson models, you can unlock only by connecting them to a PC using special cables and software.

The safest way to get your unlock code is from your carrier. T-Mobile, for example, will provide codes 90 days after you subscribe. Cingular generally doesn't help customers unlock phones, but makes exceptions on a case-by-case basis, says spokesperson Ritch Blasi. Sprint won't unlock phones--period. (Verizon Wireless says its CDMA handsets are unlocked.)

If your carrier refuses to help, third parties will sell you unlock codes for about $30 and up; a Google search for "unlock phone" produces links to Bongo Wireless, GSM Locker, and Mobile Fun. Many of these outfits are Web-based, but independent brick-and-mortar shops are preferable because you can walk in and talk to a person if there's a problem. Whatever company you use, make sure it's legit: Find a contact number, and call a sales rep to get details such as cost and service guarantees. If the unlock code doesn't work, will you get your money back? What will the company do if the unlocking procedure breaks the phone?

A Google search will also lead you to forums and blogs where fellow cell phone users share unlocking secrets--for example, Howard Forums (registration required) and Treonauts, which provides unlocking tricks for Cingular's Palm Treo 650.

Some blog sites also help you circumvent restrictions on Bluetooth file transfers. For example, IrishEyes and RussellBeattie.com publish instructions on how to unleash some of the Bluetooth powers of Verizon's Motorola V710 handset.

It's tough to know who really makes anything these days. In an era of shrinking profit margins, major companies such as Dell and HP often save money by outsourcing much of the design and assembly of their products to a small number of less-well-known (and usually overseas) companies--sometimes the same companies that supply cut-price competitors.

For example, most vendors selling LCD monitors don't make their own LCD panels. Dell buys the panel in its 24-inch wide-screen 2405FPW from Samsung; HP gets the panel in its L2335 monitor from Philips. A handful of companies provide the basic engines for most CD and DVD recorders, as well.

Does this mean that, say, your NEC monitor is no better than the Brand X model made with the same panel, or that your Sony DVD burner is no different from a no-name burner made with the same optical-drive engine? Not necessarily. The answer depends mainly on the type of product you're buying.

With LCD monitors, for example, vendors have many ways to add features and enhance the overall quality of the product. A company like Dell or HP can afford to invest a lot more than a no-name outfit can in the industrial design, the physical adjustment options, and the user interface for tweaking the monitor's setup.

For more commoditized products--items such as optical drives, where the form factor is constrained and where prices have dropped so low that there's little profit margin for manufacturers to compete over--the big-name vendors don't have as great an advantage. Of course, there will still be important differences in various vendors' warranties, tech support, and software bundles; however, the performance of two products based on the same engine should be quite similar. In that case, you should be able to get good value by choosing a high-quality product regardless of the brand name, such as one of the top-performing, inexpensive drives on our Top 10 DVD Drives chart.

Sometimes the best e-mail and chat support in the world is no substitute for a conversation with a real person. But that kind of talk isn't cheap, so to cut costs, Net-based companies like Amazon often make their phone numbers hard to find. Not to worry: A site called Cliché Ideas has dug them up:

- Amazon: 800/201-7575

- EBay: 800/322-9266

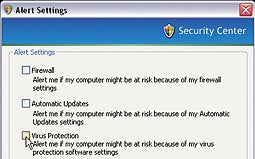

I keep my Windows system pretty well secured, but somehow that doesn't prevent Windows' Security Center from informing me that 'Your computer might be at risk' every morning when I turn on my computer. That message gets old fast. To banish it for good, go to Start, Control Panel, Security Center. Then click Change the way Security Center alerts me in the resources box and uncheck all of the boxes on the resulting screen.

Today's game consoles are powerful, crammed with useful technology, and (to habitual PC buyers) relatively inexpensive, so it's no surprise that hackers are constantly finding new ways to make them do more than just play games. The Xbox, for example, is essentially a PC with specialized graphics and audio hardware and a CPU that's a few generations old. With some dedicated hacking you can install Linux on it and use it as a PC. See Xbox Linux Project's step-by-step guide for answers to any questions you might have. (I did not find a similarly simple way to turn an Xbox into a Windows PC.)

Within a week of its release, Sony's PlayStation Portable had been hacked to let the user customize its background images and browse the Web using a secret browser built into the game Wipeout Pure. The PSP Hacks site has the story on this and other PSP hacks, including the continuing effort to allow the device to run home-brewed software. At press time Sony had just released a firmware upgrade that adds a Web browser and customizable background images, but locks out the latest home-brew hacks. Count on hackers to find a way around that eventually.

Apple doesn't make it easy to employ your IPod to duplicate your music collection on both your work and home PCs, but you can do it. If you have a Windows machine, simply plug in your IPod, find it listed in Windows Explorer, and make sure your machine can view hidden files.

Open the 'IPod_Control' folder and copy the 'My_Music' folder to your PC. Import those tracks into ITunes and put them in order there. Select Edit, Preferences, and choose the Advanced tab. Select a location for your music library by clicking the Change button, and then check Keep iTunes Music folder organized.

Utilities such as the $15 IPodRip--available for PCs and Macs from The Little App Factory--can help automate this process.

Follow the directions at Paul English's Find-A-Human IVR Phone System Shortcuts site to reach a human operator at any of more than 60 cell phone, PC, and travel firms.

Today's digital audio players and other portable devices often feature two levels of "off." One--a standby mode that allows the player to turn power back on quickly after a period of inactivity--keeps some of the player's circuits active and constantly draining a bit of power. That's what Jan Schuppius and several other members of Creative Labs' MP3 support forum found was reducing the battery life on their Zen Micro players from 12 hours to fewer than 6 hours. (Click here for their analysis.)

Creative fixed that problem in early July with a firmware update that lowered the standby time to 4 hours before the device shuts down fully, but I found the same drawback with an IRiver H10 I've been testing. Device manufacturers could follow Creative's lead in lowering standby time or correct this issue by permitting users to completely power down their players. Given the choice, many would opt for longer battery life.

Not all zoom is created equal. While optical zoom uses the camera's lens to increase magnification, digital zoom uses software built into a camera to magnify a subset of an image captured by a lens. The software does this by upsampling (or interpolating) pixels--generating new image data based on samples from the original pixels. That process can degrade the quality of the photo, making it blurry and pixelated. Optical zoom is the important number to look for.

An LCD's response time is supposed to tell you how well a monitor will respond to fast-moving images. Unfortunately, LCD manufacturers measure response times in so many different ways that the figures they quote are pretty much useless, as we found out in "LCD Specs: Not So Swift." And contrast ratios aren't much use either. In June 2003, we found monitors that underperformed their ratings by more than 50 percent.

Speaker manufacturers have a bag full of tricks they can use to inflate the power ratings of their speakers. But wattage should be pretty low on your list of deciding factors, especially for PC speakers. As any audiophile will tell you, there's no substitute for a good listening test when you're shopping for speakers. So put down the spec sheet, pick up a CD you're familiar with, and listen before you buy. If you insist on comparing speaker specs, look for a figure labeled Watts RMS that's broken down by channel instead of combined into a number representing total system power.

Hard-drive marketers like to push big numbers, such as a drive's burst transfer rate. But that number has little meaning. A typical Serial ATA drive can transfer bursts of data at 150 MBps when exclusively writing to or reading from its cache. But that doesn't happen often. A drive's sustained transfer rate or internal transfer rate (usually around 65 MBps), has more bearing on performance.

source: http://pcworld.com/resource/printable/article/0,aid,122094,00.asp